Winter Descends

The deer coats are really different now. It’s my understanding that for winter they grow a special under layer of hollow hairs that trap warm air against their skin. I’ve also heard that they have a capacity to “feel less” in their legs. I know poultry and other birds have particularly cold hardy legs because their legs have little blood supply and because of how blood supply there works, the specifics of which I’ve forgotten. It’s basically a little HVAC system. And I know some plants have mechanisms by which they pump water out of their cells to avoid freezing or to minimize desiccation. It makes sense deer would have their own specific adaptable physiology. In an article on NorthAmericanNature.com, mammologist Bryan Harding claims deer bodies can redistribute heat to the more critical parts of their bodies during the cold, i.e. from legs to organs, for example. He also says their foot pads harden to help with navigation of icy winter terrain.

I was glad to learn that at least some of deer’s seasonal body changes are light based, i.e. day-length. As I write this in 2022, Pi needs to be bulking up and she doesn’t need to be slow getting her winter coat because of the exceeding long summer we’re having. We often have light snow showing up this time of year, but this year in October, we’re at 80 degree daytime highs and overnight lows in the 50’s. That’s why I’m glad it’s not temperature that steers the deer physiology during the fall. Light on the pineal gland is in a command role. As light decreases, changes are signaled. It’s the same mechanism that controls poultry’s egg laying process, halting egg production during the low light and short days of winter and sparking it into high gear come spring. Humans have a pineal gland, too. A small one. It also tracks the diurnal light and is involved in releasing melatonin.

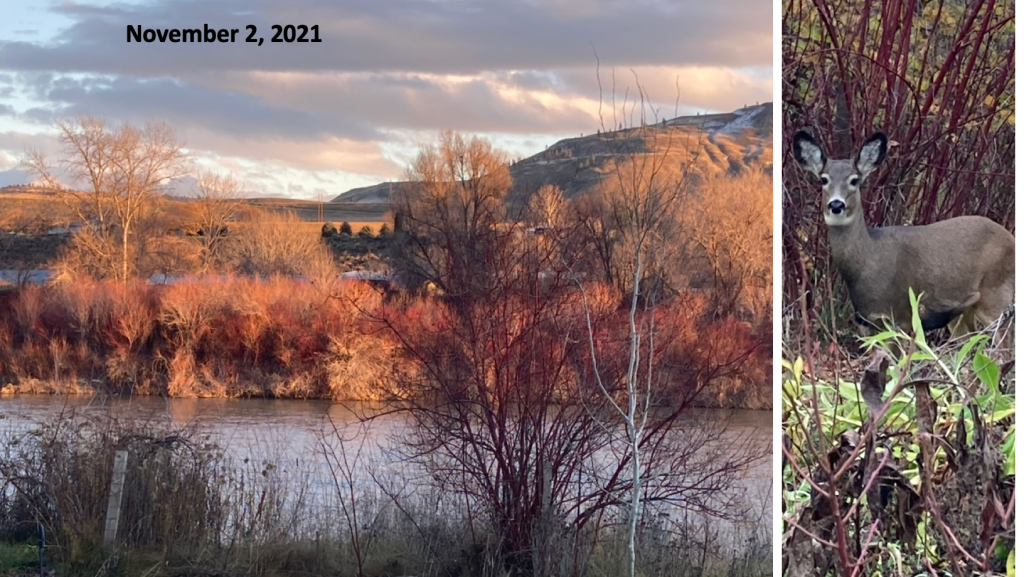

As winter comes, especially after snow falls, the deer from the Elmway neighborhood mostly disappear from my place but are regularly seen browsing landscape shrubs in town and I’d guess they’re hitting the orchards and any wheat or alfalfa fields they have access to south of Okanogan or up on the flats. But what about water during the frozen months? Deer can and do consume snow, but seems it would take quite a bit of work to consume enough snow to meet water needs. Harding’s previously noted article discusses how deer biology helps them conserve water during winter, for example, “drying” their feces prior to elimination, allowing the body to re-use that fluid. I know that deer sweat very little and mostly pant to dissipate heat, so not sweating would also conserve water. Harding also talks about changes in winter metabolism, i.e. lowering heart rates, energy use, digestion, etc. I’ve watched hens and roosters do this. They experience a state of deep torpor when sleeping in the winter cold, which is about as close to hibernation as an animal can get without fully hibernating. Their heart rates slow, breathing slows, energy use slows. During torpor, you can pick a rooster up and trim his spurs or treat a wound or dress him in a fancy little outfit if you want, and he won’t even notice.

In terms of warmth, I assume deer find the warmer micro-climates in their range, and I’ve read about deer-yards, “circular” paths walked by deer families or a herd between a set of trees and other natural shelters and browse areas. Such yards facilitate browsing, keep the deer together for warmth and safety, and create space where they don’t have to always plunge through snow. At the lower elevations the Pogue deer use, I’m not sure there’s the ecology for yards, but in more forested or shrubby areas, there would be. Actually, there are places on the river well populated with poplar in addition to shrub. Those kinds of spots would “yard” well. Deer definitely find and use the paths I shovel in the snow during brief winter visits.

Here, like the slo-mo flood waters, the snow can start slowly some years. Snow is going to impact feeding. I would imagine that’s an added challenge for Pi, but merely from watching the rate at which fawns grow, it’s clear deer bodies can make excellent use of food. I assume they also work at conserving energy during winter, living on their fat stores, minimizing travel, maximizing “resting.” And good lord, these animals are eating wood. Wood. Not just leaves. Wood. Even if it’s twigs and the more tender tips of branches, that’s still wood. Go ahead. Go try to eat some wood and see how far it gets you. Amazing.

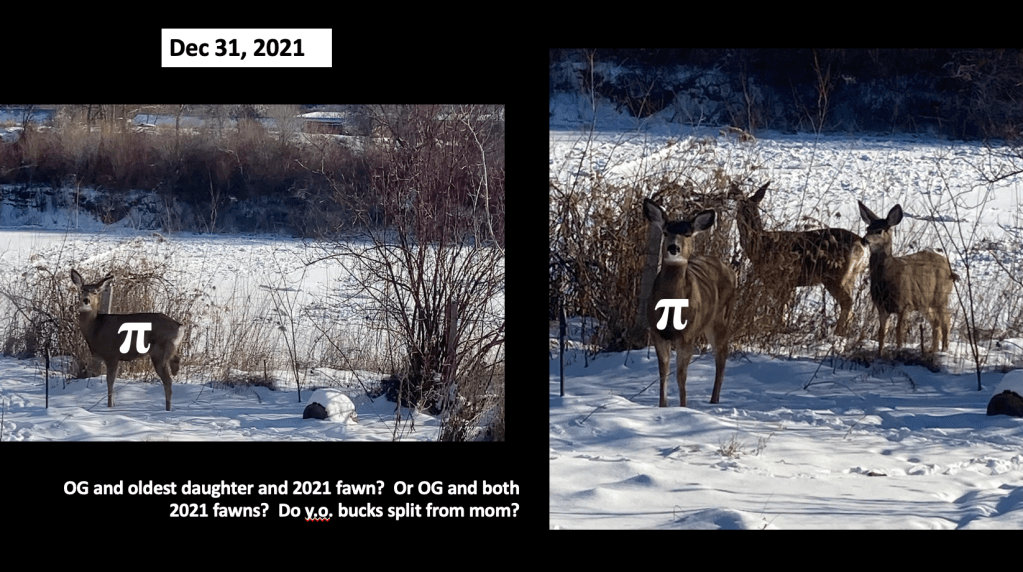

In December 2021, we experienced a 140 degree difference from the temperatures of the Heat Dome in June. We went from 120 to 20 below. Despite knowing that animals— who again, are the places where they are— despite knowing they’re suited for life in the outdoors, we hit some pretty tough temperatures for about a week, and I thought of Pi. I’m assuming as she continues to age, she’s at risk of increasing atrophy in areas of her body associated with her partial limb. Regardless how prepared animals are for it, cold has to be a stressor. But there she was, showing up in the middle of our deep freeze and looking pretty good.

As the questions I forgot to remove from the photos above note, I think Pi is with her two fawns, but can’t definitively identify them. Where’s the Auntie? It’s clear who Pi is but those winter coats are otherwise deceiving.

And how’s her agility? Her endurance? She looks pretty good whipping around a snip of fence onto the river bank.

It’s not completely out of the ordinary to get some big snow dumps here though we also experience streaks of mostly mild winters, one of which was apparently ending. Just a couple weeks after the deep freeze, we got dumped on. Left photo above shows a deluged path leading to the patio area. Photo with the vehicle is near another well used path. This was snow that landed on top of a lesser base of snow, but a snow base that had also drifted. Drifts were definitely part of these pics, but a hundred miles south of the Elmway neighborhood, the town of Leavenworth got three feet over night on top of a 2 foot base. National Guard was sent to help. I wondered again about Pi. But as is common here on the river, once it snowed, the cloud cover warmed things up and there was at least some melt pretty quickly. Meantime, I was just cutting paths everywhere, and I wasn’t only one using them.

She showed up about a week after the snow hit, but not again until the following summer.

And that’s year one with the O.G.

Next Post: A Fawn is Born

Leave a comment