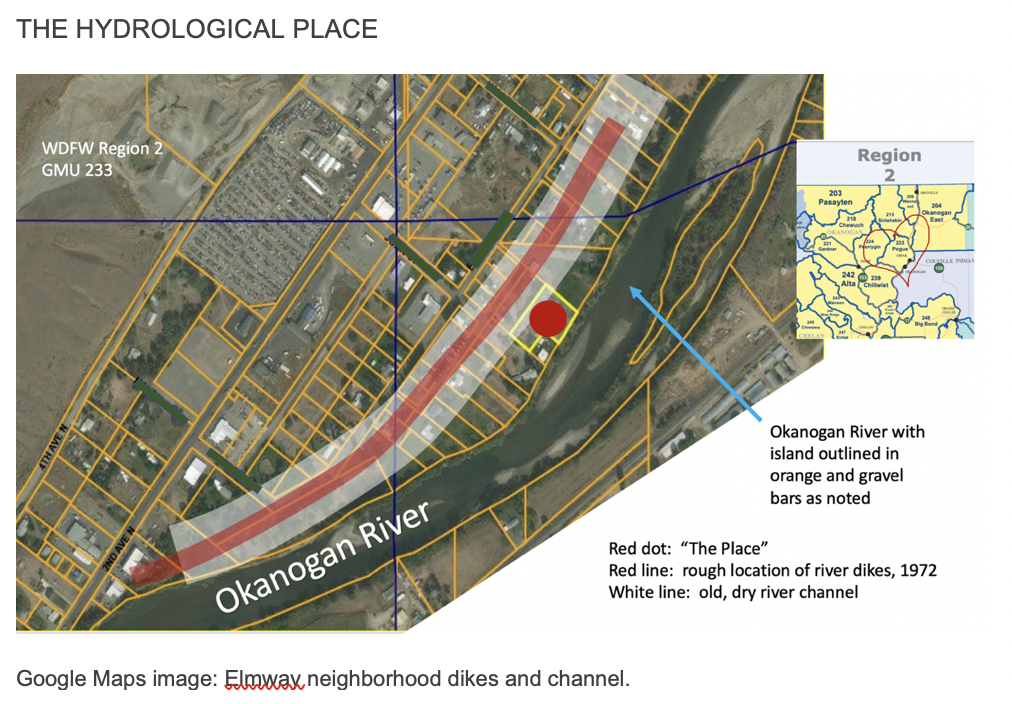

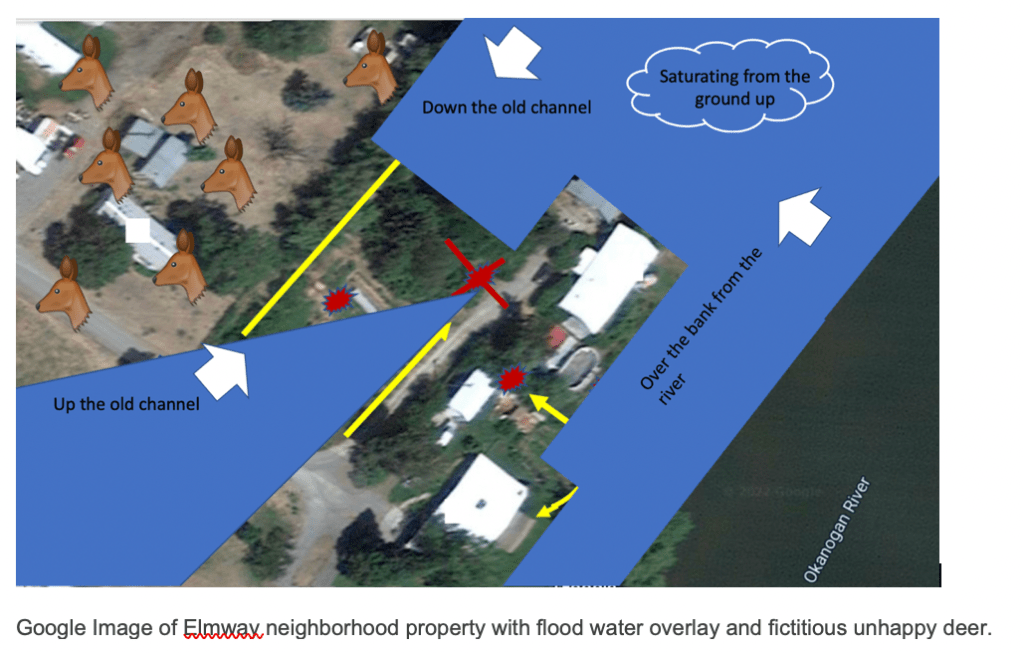

Zooming in on one of those prior Google Images, this is the Elmway neighborhood. The white swath is a dry river channel formed some time back when the river had a slightly different or larger flow. The red line marks a dike system put in place during the big 1972 flood. It might seem odd to have imprisoned the Elmway neighborhood on the flood side of the dikes, but most of the neighborhood is considered “indefensible” in emergency management terms because it saturates. Water comes up over the banks, yes, but also just percolates up out of the ground in that areas. Dikes can’t do anything to stop saturation out of the ground. They were intended to protect valuable business property and critical roads right outside the neighborhood. Army Corp built them and left them for property owners to maintain. Or not. The red dot is the spot I’m watching these deer on.

Observing these deer has been a pleasure but also deepens my concern about climate, weather, and environment. Humans and animals deal with the same volatility in those arenas, but at the moment, we humans have the advantage. We can sometimes’ preemptively adjust our behavior before an event. If needed and if lucky, we can flee a fire in a vehicle filled with water and sleeping bags. The animals cannot. We can monitor developing weather and things like winter snow packs and, if lucky, take cover from tornadoes and prep for a spring run-off that looks likely to swamp something important. The deer’s relationship with chaos in the environment is a much more immediate one.

In the 20+ years I’ve been on this property, river events have occurred a few times, but only one qualified as a major flood. A high water event not noted in the chart above occurred in 1997, the second spring I lived here. It was a big deal because it had been so long since the water had been something you could call high, but it resulted in mostly just some expected “low land” and pasture flooding, and a few flooded wells. Still, it activated the public and the local emergency management folks and they and NOAA-Spokane reps held some impressive public meetings, by which I mean we learned things of value. And there was a little drama. Twenty-five years of river debris was scoured off the banks and hosed down the river in ginormous flotillas: huge logs spinning like ballerinas, dead cows floating feet up, an occasional dock sailing off on its own adventure. I wrote a temporary column about it all for a regional paper, human interests meets hydrology.

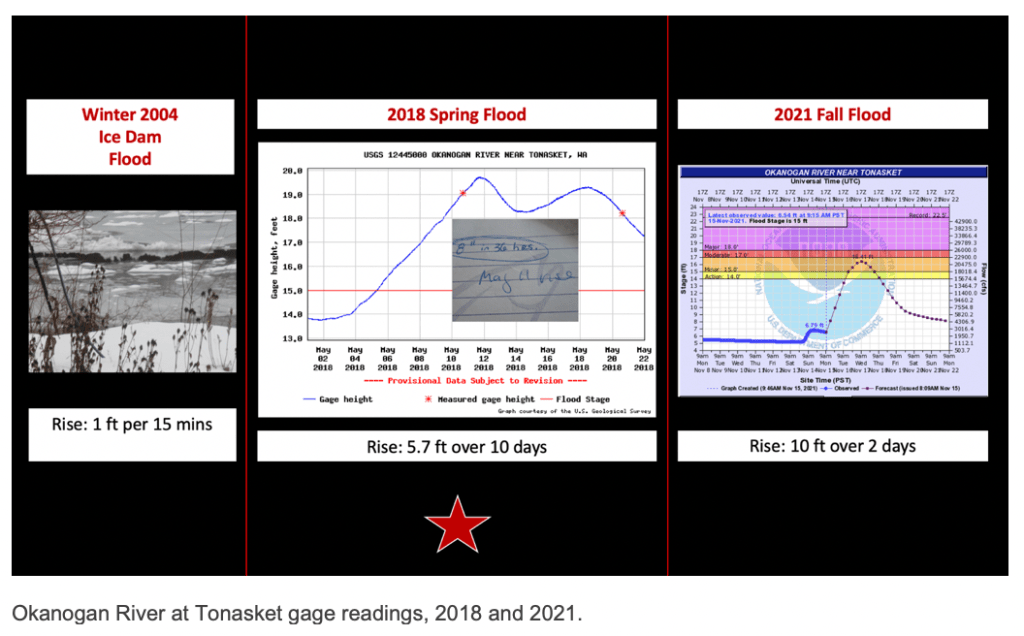

In contrast to 1997, the ice dam flood that occurred in 2004 was stunning, caused an hour of borderline terror, and resulted in zero impact. An elder neighbor who was still living at the time said that in her 60 years on the river, she’d only seen an ice dam flood one other time. She thought it was during the 60’s. The ice dam flood is a whole story itself, but briefly, an unusually warm bout of January weather caused the river ice twenty miles north of us to soften and then bust apart catastrophically about 10 p.m. one night. The exploded ice smashed its way downstream and sounded like a freight train barreling through the back yard when it got here. Half an hour later, the busted ice dammed up at a narrow in the river south of us, and for about an hour, the water backed up behind that ice dam and rose in the Elmway neighborhood at a rate of one foot per fifteen minutes. That’s a shocking rate of rise, but the eeriest part of the ice dam flood was a coyote that appeared in the middle of the river at one point, in the pounding ice, in the dark. We watched as he or she desperately leapt from ice slab to ice slab, trying to head up river but rapidly losing ground and clearly becoming fatigued.

The river was so loud the neighbors and I had to shout to hear each other standing barely ten feet apart, but when that upriver running coyote disappeared from sight down the river, it suddenly felt silent. My wildlife bio neighbor later speculated the animal had to have been crossing the river when the ice broke, maybe trying to reach family members across the river. No animal, he insisted, would’ve thrown itself into such roiling chaos without a most compelling reason. After an hour of truly frightening water rise, the river stopped and then dropped. Everyone went home to sleep. I can still see that coyote in my head.

Last November, 2021, British Columbia, Canada, was hit with multiple atmospheric rivers that flooded the province, washed away towns and highways, and isolated east BC from west. There’s a recently released film about the catastrophe, but it may only be streamable from Canada online. Link to some film info: A River in the Sky.

The river I sit on is fed by parts of those same flooded watersheds in Canada, and in fact, the Okanogan River in the U.S. is similarly sourced. In Canada, it’s the Okanagan River. Same river, just more A’s. The fall 2021 B.C. flooding pushed the water levels on the Okanogan in the US up to bank-full. Again, this was “out of the norm.” Normally, the river sits at 4 to 6 feet in height all fall and winter, but during this rare November flood, it flew from 6 feet to 16 feet in two days. Again, an impressive rise, but the Elmway neighborhood didn’t flood, and the water receded quickly because of the seasonal hydrology at play. The spring flood of 2018, however, was the real deal.

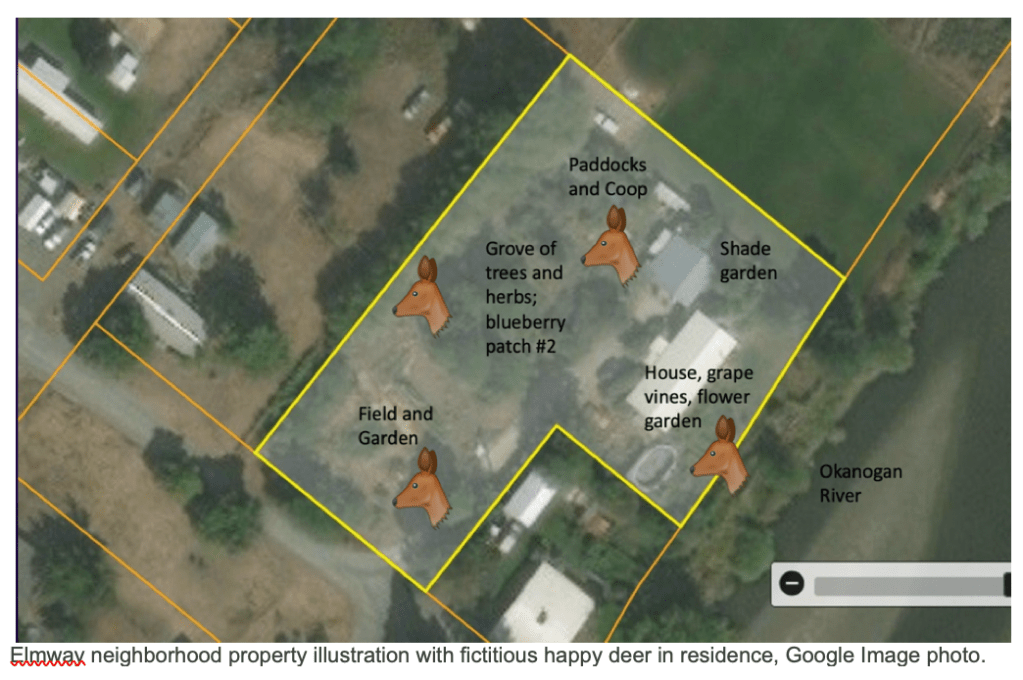

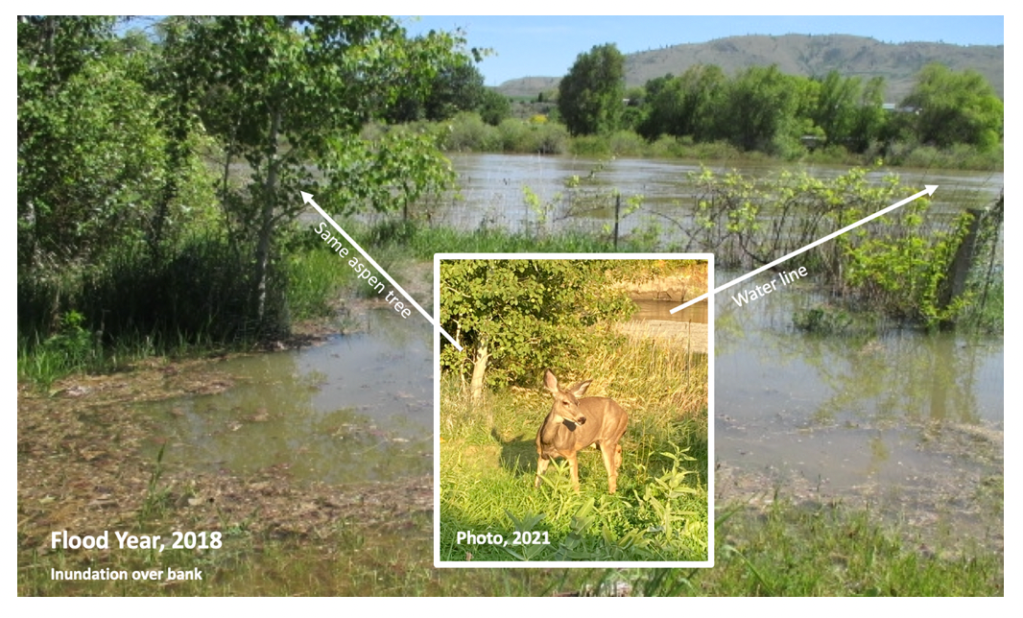

The Okanogan River is a fairly benign river when flooding in the spring, or at least it can be, and by benign, I mean only that it tends to flood “slowly.” We get a lot of forewarning in the spring and you can “see” the water coming at you from Canada for almost 48 hours before it arrives. Usually. But slow doesn’t mean gentle. In 2018, that slo-mo water rose over the banks, flowed into the old, dry channel, and saturated straight up through the ground all around us, eventually covering about 2/3 of the property on which I sit and that the deer eventually began using. The river is 115 miles long from its start in Canada to where it feeds into the Columbia River, to which it is a tributary. While I hustled trying to track and manage the flooding in a few block radius, there were deer along the a 250 mile swath of riverbank dealing with a 250 mile swath of unannounced, disrupted habitat. I wonder when and how they would have stepped back from it? Just far enough? Next “safe” spot?

The river’s rise from dormant spring levels to its crest lasted about three weeks, but much of the rest of the summer was also a wash. The spring water wasn’t a fast moving catastrophic rain storm like in 2021, but rather the full run off of snow melt from the watersheds in that feed the Okanogan River. And Canada had some snow packs up to 300% of normal that year. That’s a lot of water. After cresting, the river sat at flood stage for almost two weeks, and then ran twice as high as normal well into August. Many river corridors and much flora was impacted, septic systems and miscellaneous trash flowed into the river, wells were contaminated, structures and roads flooded, etc. Riverbank terrain these deer relied on were pretty unusable during spring/summer of 2018, but it wasn’t something I was tuned into then.

Does could not have birthed their fawns in their hidden spots along the river that year, and the nearby human-occupied part of their range was congested with emergency personnel, swarms of volunteers filling sandbags from mountains of sand dumped in parking lots, lots of big trucks, lots of road detours. Presumably, any riverbank dwelling deer that year vacated quickly and thoroughly, but here’s a couple views of the disruption the residential deer would have experienced had they been on my particular little home plot during this flood.

Left photo faces south down an old, dry channel during a “normal” year. The gravel is my drive. Right photo is the same spot from May 2018, during the flood. Channel was flooded for its whole length south inside the dike. Deer in photo 3 is standing in the same driveway, facing the channel, but in a non-flood year. The channel would’ve still been unusable into June, well into fawn season. The newborn that was brought here in 2022 walked up that channel to get here.

In the two top photos above of the field and garden area, an overhead wire helps mark the comparisons. The fawn in the center photo is standing in 2022 in what would have been the 2018 flooded area bottom left. The shed behind her is the same one in the previous driveway photos. There was no gardening that year, just a big influx of weed seed floating in and decades of buried pigweed and cochia seed floating up out of soil. The cheet grass drowned, which was nice, but it rebounded fully the next year.

On the plus side, this piece of land hadn’t been watered so well in 50 years. Permanent plantings loved it. Trees shot up in height. The strawberries were the size of your fist, though we couldn’t eat them because they were standing in contaminated flood waters. Permanent beds and perennials survived just fine, but the water shaped some landscape changes here and directly impacted property management post-flood.

The back yard (the river-side yard) flooded extensively. I actually stopped looking because it was unnecessarily unnerving, and the real focus was out front monitoring the water in the dry channel encroaching on the only way in and out of our little spot. In the inset photo above, a buck stands in the backyard where a buck would not stand during a flood year if he could avoid it. I don’t think he’d have stuck around for that nonsense. These are not Marsh deer.

This 2018 water along the north side of the house is in a little patio area with multiple sidewalks in and out of it. Flooded sidewalk on left is where the fawn stands in the pic on the right (2022). The fawns love this spot. The little concrete paths lure them in. The area sits next to a main path the deer use to navigate the north line of the property and up and down the normally dry channel. Deer would have had no access safe access through the Elmway neighborhood in 2018.

Next: Fire and Heat

Leave a comment